|

Firstly

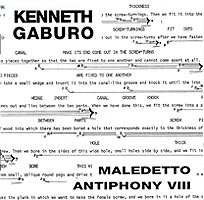

conceived in 1967-68, "Maledetto" is a composition for seven virtuoso

speakers that sounds as modern as anything in the last five years, a commanding

statement by a largely ignored composer. What Kenneth Gaburo declares in the

notes is essential to comprehend the aesthetic significance of this work: "One

can view each human as a unique and complex linguistic system, capable of generating

more than one kind of language at a time (Š) Thus each human can be viewed

as a contrapuntal, rather than a mono-lingual system". This explains just

about everything. The building block at the core of this piece is the word "screw"

in its various connotations, both in terms of meaning and sonic structure; from

that, a whole edifice of intersecting expressions is raised, up to a point in

which the attentive listener gets gradually pushed away from any theatrical

interpretation of the score (which, oddly enough, is indeed part of a six-hour

theatre performance) to enter a thoroughly musical realm, the voices perceived

as assorted typologies of unusual instruments. Over the course of these 45 minutes,

whose complexity can't possibly be illustrated by a sheer review, we're literally

immersed in technological imagery and, above all, bodily reactions, either described

or simply perceptible (sibilance, syllables, breath, chuckling, call-and-response).

As Warren Burt rightly states, this is "a deep and profound celebration

of the body, the physical, the sexual". The power of this material just

overwhelms the other music contained here, even though the latter deals with

the important issue of people reacting to the notion that "nuclear war

has made their lives expendable". A percussionist interacts with tapes

of individual views (or non-views) about the main topic along the lines of a

dramatic performance that should be seen live for better understanding. Having

the gravity of the implication been established, there's not a single minute

of the (still interesting) "Antiphony VIII" that equals the emotional

and technical intensity of "Maledetto" which alone is worth of the

purchase of this disc, as it's definitely indispensable listening. -Massimo

Ricci Firstly

conceived in 1967-68, "Maledetto" is a composition for seven virtuoso

speakers that sounds as modern as anything in the last five years, a commanding

statement by a largely ignored composer. What Kenneth Gaburo declares in the

notes is essential to comprehend the aesthetic significance of this work: "One

can view each human as a unique and complex linguistic system, capable of generating

more than one kind of language at a time (Š) Thus each human can be viewed

as a contrapuntal, rather than a mono-lingual system". This explains just

about everything. The building block at the core of this piece is the word "screw"

in its various connotations, both in terms of meaning and sonic structure; from

that, a whole edifice of intersecting expressions is raised, up to a point in

which the attentive listener gets gradually pushed away from any theatrical

interpretation of the score (which, oddly enough, is indeed part of a six-hour

theatre performance) to enter a thoroughly musical realm, the voices perceived

as assorted typologies of unusual instruments. Over the course of these 45 minutes,

whose complexity can't possibly be illustrated by a sheer review, we're literally

immersed in technological imagery and, above all, bodily reactions, either described

or simply perceptible (sibilance, syllables, breath, chuckling, call-and-response).

As Warren Burt rightly states, this is "a deep and profound celebration

of the body, the physical, the sexual". The power of this material just

overwhelms the other music contained here, even though the latter deals with

the important issue of people reacting to the notion that "nuclear war

has made their lives expendable". A percussionist interacts with tapes

of individual views (or non-views) about the main topic along the lines of a

dramatic performance that should be seen live for better understanding. Having

the gravity of the implication been established, there's not a single minute

of the (still interesting) "Antiphony VIII" that equals the emotional

and technical intensity of "Maledetto" which alone is worth of the

purchase of this disc, as it's definitely indispensable listening. -Massimo

Ricci

A dangerous man: To Gaburo, language, life and music should not be separated.

In terms of his potential marketability, Kenneth Gaburo could easily have matched

John Cage. Both, after all, had a talent of finding demonstrative phrases and

striking musical forms for their ideas, which allowed even the average Joe to

grasp what they were on to – in the somewhat unlikely even of him being

interested in finding out, that is. Their respective oeuvres were marked by

a peculiar penchant for allowing the public to either dismiss them as fluff

or lift them to a metaphysical plateau where journalistic criticism and mainstream

rejections could no longer reach them. Depending on one’s point of view,

too, it was even possible to make out revolutionary tendencies beneath the surface:

Just as with Cage, Gaburo’s musical ideas implied radical changes in the

way that art should or could be perceived – and in the way it was being

sold to the public.

To Gaburo, language and music should not be separated. Nor should performance

and reception of art. From his point of view, a piece did not begin on stage,

but during the very first rehearsal – something he would take to extremes

on “Maledetto”. Percussionist Steve Schick, meanwhile, who performs

“Antiphony VIII” on this disc, a piece which requires the soloist

to pass through emotional states of ignorance and anger to exhaustion, can still

acount how the composer moved his instruments farther apart only moments before

the concert was to begin.

The reason was simple yet stunning: Schick had become too proficient in playing

the music. His gradual breakdown had turned into acting instead of real physical

fatigue. For Gaburo, it didn’t matter whether or not the public could tell

one from the other, because the music, as it was conceived by the score, only

came into being by ignoring any external observer, existing for it’s own

sake and within its own space. If l’art pour l’art were a doctrine,

even James Joyce would seem like a liberal in comparison.

Quite obviously, Gaburo’s principles and beliefs were much closer connected

to theatre than to music. In a dramaturgical play and in the hands of capable

actors, the process of pretending turns into something real, after all, and

words still have the power to shape worlds. So it was, too, with Gaburo, whose

„Maledetto” spans a 45-minute long cosmos of monologues, dialogues

and multilogues, screams, sylables and streams of thoughts, debates, dreams

and dada.

On the outside, the work is a lingual discussion of the term “screw”

in all of its connotations as well as a onomatopoetic dissection of its sounds.

Musically, it constitutes a fantastically immersive experience and a hypnotic

ritual for eight voices and a short opening section of rustling hiss. Everything

bases on language rather than meaning and logic here, yet language can not exist

on its own accord. Only in the moment of utterance, when the words leave the

lips of a performer, does it become real. In this instance, too, the liberation

from the need to make sense introduces a feeling of limitless wideness and endless

possibilities: You could gladly get lost in this piece for hours.

Leading up to its premiere, Gaburo had practised with the particapating performers

for months and by the time the version on this album was recorded, the cast

had already grown in experience and confidence. And yet, everything sounds fresh,

naive even, as if the vocalists feel their way forward towards making contact

and establishing relationships as if they were meeting for the first time.

Gaburo's art rejected passive consumption, demanded participation and therefore

opposed the traditional and proven business model of mass marketing music to

uncritical hordes of buyers. Its logical consequence was that if language was

music and life was a form of art, then everyone could be an artist. In a world,

which mostly regards music as a tightly delineated, restrictively defined comfort

zone, Kenneth Gaburo was a dangerous man. No wonder John Cage, whose ideas could

be still be dismissed as humurous and whimsical, eventually eclipsed him in

medial terms and in musical history.- By Tobias Fischer, Tokafi

|